Cornbread and ‘Sow Belly’

Food, or lack of it, was almost always on the minds of Confederate soldiers and no food was as prevalent as cornbread, sometimes accompanied by a meat ration of beef or pork. Soldiers referred to pickled beef as “salt horse” and pork as “sowbelly.” Many soldiers got so tired of cornbread that their feelings were summed up by one who wrote home: “If any person offers me cornbread after this war comes to a close, I shall probably tell him to—go to hell!” The beef was so bad it often was described as “blue” and so clammy that it would stick to a wall or tree if thrown against one. One soldier wrote that the meat was so full of maggots that “we had to have an extra guard to keep them from packing it clear off.” Sometimes bacon had to be eaten raw because of lack of time for cooking.

Army regulations of 1857 called for a daily allowance for each soldier of 12 ounces of pork or bacon, or one pound and 4 ounces of salt or fresh beef. Also, the soldier was to receive one pound and 6 ounces of soft bread or flour, or one pound and four ounces of corn meal. Another food item frequently supplied by the Confederate government was molasses. It was frequently poured on “slap-jacks,” Johnny cakes and cornbread and used as a substitute for sugar. The regulations also called for periodic distribution of such things as beans or peas, rice or hominy, sugar, salt, and coffee.

Army regulations of 1857 called for a daily allowance for each soldier of 12 ounces of pork or bacon, or one pound and 4 ounces of salt or fresh beef. Also, the soldier was to receive one pound and 6 ounces of soft bread or flour, or one pound and four ounces of corn meal. Another food item frequently supplied by the Confederate government was molasses. It was frequently poured on “slap-jacks,” Johnny cakes and cornbread and used as a substitute for sugar. The regulations also called for periodic distribution of such things as beans or peas, rice or hominy, sugar, salt, and coffee.

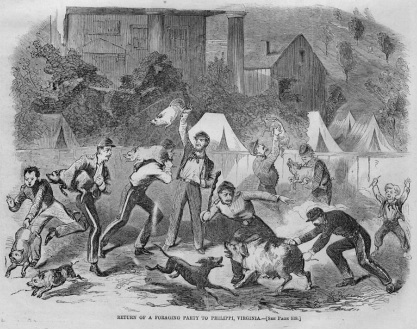

Foraging

Foraging party in Philippi, 1861 (Harper's Weekly)

The Confederacy was unable to retain the 1857 ration, making almost immediate reductions in meat and substitutions or elimination of several other items. The quality and quantity of rations varied with changing circumstances. Often government-issued food was scarce or non-existent during times of actual campaigning. At those times, soldiers foraged for whatever they could obtain in the surrounding countryside. Any chickens or pigs that wandered into the paths of soldiers quickly were “confiscated,” as were eggs, milk and other commodities found on nearby farms.

Apples, cherries, strawberries and nuts were eagerly seized by hungry Confederates, although the consumption of green apples, half-grown peaches, unripe blackberries, tree buds and even boiled grass could cause severe cases of diarrhea or dysentery. From time to time soldiers had to exist for days on parched corn, often shucked from the cob and frequently still green.

Vegetables were a major deficiency in the Confederate diet. Irish potatoes and dry peas were issued now and then, and greens and other fresh vegetables were dispensed on rare occasions. But scurvy was a constant threat in the Confederate army, and from time to time officers sent the men out to collect such things as wild onions, water cress, dandelions, artichokes, poke shoots and similar “greens” to ward off the disease.

Peanuts, or “goober peas,” grew in much of the South, thriving in sandy loam and warm temperatures. Confederate soldiers ate quantities of them and one of the more popular comic songs rendered by the soldiers was “Goober Peas.”

Coffee was rarely issued to Confederate troops, and soldiers tried to brew it from such items as parched peanuts, potatoes, peas, dried apples, corn and rye. None of the substitutions were all that palatable, and the best alternative for coffee came from trade with Union troops (tobacco was easily obtainable for Confederates, who often exchanged it for the genuine coffee and sugar usually in ample supply for Federals). Coffee and sugar also were taken from Federal prisoners, or were seized along with other edibles from haversacks of Union dead on the battlefield.

Food seized at captured Union supply depots or taken from captured or dead Federals after a battle included a number of canned items such as desiccated vegetables (termed by the soldiers “desecrated” vegetables). These were a mixture of many sorts of vegetables pressed into small bales in a solid mass, which would swell up when water was added for cooking. Woe to the soldier who ate a portion dry and followed it with drinks of water.

Apples, cherries, strawberries and nuts were eagerly seized by hungry Confederates, although the consumption of green apples, half-grown peaches, unripe blackberries, tree buds and even boiled grass could cause severe cases of diarrhea or dysentery. From time to time soldiers had to exist for days on parched corn, often shucked from the cob and frequently still green.

Vegetables were a major deficiency in the Confederate diet. Irish potatoes and dry peas were issued now and then, and greens and other fresh vegetables were dispensed on rare occasions. But scurvy was a constant threat in the Confederate army, and from time to time officers sent the men out to collect such things as wild onions, water cress, dandelions, artichokes, poke shoots and similar “greens” to ward off the disease.

Peanuts, or “goober peas,” grew in much of the South, thriving in sandy loam and warm temperatures. Confederate soldiers ate quantities of them and one of the more popular comic songs rendered by the soldiers was “Goober Peas.”

Coffee was rarely issued to Confederate troops, and soldiers tried to brew it from such items as parched peanuts, potatoes, peas, dried apples, corn and rye. None of the substitutions were all that palatable, and the best alternative for coffee came from trade with Union troops (tobacco was easily obtainable for Confederates, who often exchanged it for the genuine coffee and sugar usually in ample supply for Federals). Coffee and sugar also were taken from Federal prisoners, or were seized along with other edibles from haversacks of Union dead on the battlefield.

Food seized at captured Union supply depots or taken from captured or dead Federals after a battle included a number of canned items such as desiccated vegetables (termed by the soldiers “desecrated” vegetables). These were a mixture of many sorts of vegetables pressed into small bales in a solid mass, which would swell up when water was added for cooking. Woe to the soldier who ate a portion dry and followed it with drinks of water.

Shipping and Spoilage

Hardtack and Johnny cakes (CS Monitor.com)

The South, as an agricultural nation, produced plenty of foodstuffs for its soldiers, but lacked the transportation and storage facilities to get them to troops in the field in sufficient quantities and in quality shape. The Confederacy’s railroad system was never equal to war needs and after 1862 deteriorated rapidly from its inability to replace worn-out rails and rolling stock. Commissary officers also frequently lacked the funds to procure supplies, as many producers would hold their crops as long as possible to take advantage of ever soaring prices. There also was a shortage of boxes, kegs, sacks and barrels to pack provisions for transportation. And sometimes salt was lacking to preserve meat.

Some Confederate soldiers were fortunate enough to receive packages from home, though Upshur Countians in the 25th Virginia were usually cut off from that supply. The most frequent requests for home shipments involved vegetables and sweets. Many of the home shipments were lost in transit or were in such bad shape as to be inedible when they arrived. Some that arrived safely spoiled in storage during active campaigning. Soldiers could buy food from nearby farmers or from sutlers (storekeepers) when available—if the soldier had the money to purchase it.

Hardtack (hard crackers) was sometimes issued by the Confederate government or was obtained from Federal sources. But the crackers were so hard they could be deadly to teeth and gums unless soaked in water (or heated broth) and pounded into softer pieces with a musket stock. Also, hardtack that had been stored for long periods frequently was “inhabited” by vermin and was referred to by soldiers as “worm castle.”

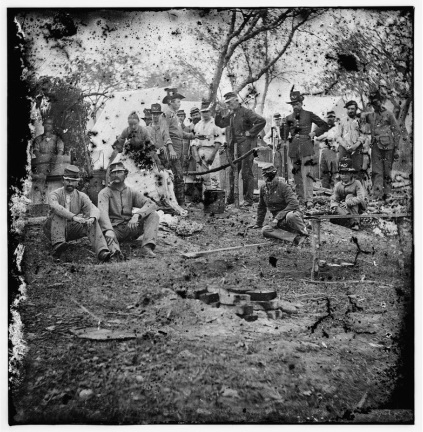

“Chatting with my mess-mates, passing time away…”

Courtesy of Hungryhistorians.com

What food Confederate soldiers had was poorly prepared for the most part early in the war. Cooking usually was done in “messes” made up of four to eight men drawn together by ties of kinship or congeniality. They took turns at cooking, cleaning skillets and performing other duties in preparing and serving food. As time went on, some of the messes became proficient at preparing nutritious and tasty food from what was available.

At least one soldier in each mess normally carried a skillet and some carried a plate of some sort. A few had a fork or spoon, but most depended on pocket knives, sticks and fingers for their eating utensils. When flour was available, bread was kneaded on boards, oil cloth, shirt tails or any other flat surface available. Sometimes flour dough was wrapped around a ramrod and turned over the fire until brown. Both cornbread and wheat bread were often cooked on a board slanted near the fire—time permitting. Corn on the cob and potatoes were baked in their jackets beneath heaps of glowing embers. However, empty stomachs often dictated against the slower processes of preparing food.

Perhaps the constant hunger pangs of a Confederate soldier were best summed up by one who wrote to his father that when he returned home, he intended to “take a hundred biscuit and two large hams, call it three days rations, then go down on Goat Island and eat it all at ONE MEAL.”