Why They Fought

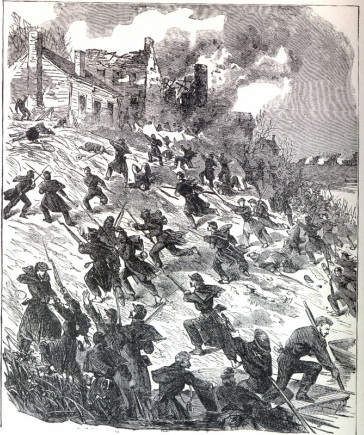

Storming Marye's Heights at Fredericksburg, Virginia (Dec. 13, 1862).

There were probably as many reasons why the Civil War soldier was willing to fight as there were soldiers, but a few reasons stand out.

Slavery is often given as the principal cause of the war, and there is no doubt that it was a major factor in the minds of some soldiers — Northern and Southern. But it was not mentioned often in letters and diaries by the fighting man until the Emancipation Proclamation became a subject of discussion in the middle of the war. Some Union soldiers had abolition as an object from the beginning, and others became more vocal about it by late 1862. But a number made it clear throughout their experience that freeing the slaves was not a major purpose of their fight. Rather, the principal cry of Northern soldiers was to preserve or restore the Union.

Likewise, Southern soldiers seldom listed defense of slavery as one of their main reasons for fighting. Southern soldiers in particular fought more to defend their homes from the “invaders,” whether their homes were close the battlefield or hundreds of miles away. This was mentioned frequently in diaries, letters and such. And many a Southern “deserter” during the war, especially in the latter stages, returned home temporarily or permanently to protect his family as well as he could. Deserters, of course, were subject to execution if caught.

States Rights

States Rights sometimes has been downplayed by historians and others as a principal cause of the war, yet it was frequently on the minds of soldiers in their letters and diaries. States rights had been prominent in debates between North and South since colonial days, had played an important part in the writing of the U.S. Constitution, had been prominent in the New England (Hartford Convention) movement to secede from the Union during the War of 1812, and was behind the Nullification crisis with South Carolina in 1832. Even if the political aspects of states rights weren’t uppermost in the minds of some Southerners who chose the South in 1861, family and regional ties often were. Robert E. Lee, when deciding whether to accept an appointment to head the Union forces in 1861, came to his final decision with the statement: “With all my devotion to the Union, and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home.” Thus, he turned down the invitation to head the Union forces and eventually became the South’s most prominent General.

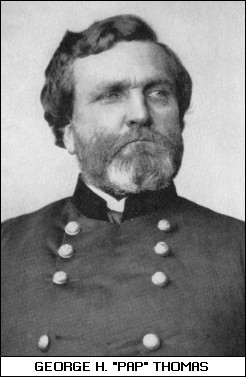

Another Virginian who struggled with the decision of which side to fight on was George H. “Pap” Thomas, who lost the support of most of his relatives and friends by choosing to remain with the Union. When asked in November 1863 whether soldiers killed at Chattanooga and Missionary Ridge should be buried according to states, he replied: “No, no; mix ‘em up, mix ‘em up. I’m tired of states rights.”

Enmity

Stonewall Jackson, wife Mary Anna and daughter (Civil War Gazette)

Was hatred of the enemy a major motivation for fighting the foe? In a number of cases, yes. Yet even that varied with the individual and the situation, and tended to lessen as the war went on as soldiers on both sides realized how similar they were to their foes. Even the fierce warrior “Stonewall” Jackson wrote to his wife on Christmas day, 1862: “But what a cruel thing is war; to separate and destroy families and friends, and mar the purest joys and happiness God granted us in this world; to fill our hearts with hatred instead of love for our neighbors, and to devastate the fair face of this beautiful world. I pray that, on this day when only peace and good-will are preached to mankind, better thoughts may fill the hearts of our enemies and turn them to peace.”

Paychecks and Bounties

Was money a motivation for fighting? Not in most cases. A Confederate infantryman was paid $11 a month in the first years of the war, a rate raised to $18 a month in June 1864 as inflation soared in the South. Northern enlisted men in the 1861 to 1864 period were paid $13 a month, with a raise to $16 a month in 1864. Officers and non-commissioned officers (sergeants and corporals) were better paid in both armies than were privates. Initially lieutenants made $105.50 a month, captains were paid $169 monthly and infantry colonels received $212 a month. Confederate corporals received $13 a month and 1st sergeants $20 a month in the 1861 to 1864 period. Soldiers were supposed to be paid every two months in the field, but were fortunate if they received their pay every four months. There were instances when the pay was delayed for up to eight months.

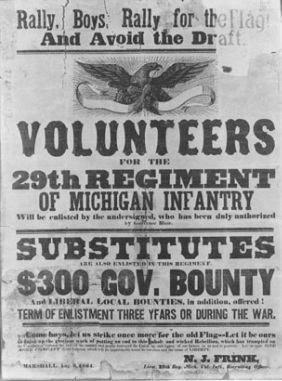

So, in neither North nor South was money a principal motivation—except, perhaps, in some parts of the North where bounties of up to several hundred or even thousands of dollars were paid for enlistment or re-enlistment in states or counties desperate for men to fill the ranks as the war continued. Many of the “bounty men” would desert at the first opportunity, change their names, and accept a bounty from another unit. Each side also allowed substitutes to take the place of men drafted, upon payment of $300 for commutation from a particular draft call to up to $1,000 for a permanent substitute. This led to complaints by common soldiers that it was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

So, in neither North nor South was money a principal motivation—except, perhaps, in some parts of the North where bounties of up to several hundred or even thousands of dollars were paid for enlistment or re-enlistment in states or counties desperate for men to fill the ranks as the war continued. Many of the “bounty men” would desert at the first opportunity, change their names, and accept a bounty from another unit. Each side also allowed substitutes to take the place of men drafted, upon payment of $300 for commutation from a particular draft call to up to $1,000 for a permanent substitute. This led to complaints by common soldiers that it was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

Pride and Camaraderie

From the beginning of the war, soldiers often fought for pride in company, regiment or brigade (geographical self-esteem being important in all sections). As the war went on, more and more soldiers fought for something much simpler — the “family” of men with which he went into battle. Having shared various privations (including lack of food, clothing, discomforts on the march and in camp, and boredom as well as fearsome battle experiences), the typical soldier was willing to enter the cataclysm of battle as a duty to his compatriots, companions, comrades.