Illness and Treatment

Civil War soldiers had a larger chance of dying of various diseases than of being killed or mortally wounded on the battlefield. The best figures available show that of 360,222 deaths on the Union side, 250,152 were due mainly to disease, while Confederate estimates (harder to determine because of the sparseness of existing records for the South) showed that of 258,000 deaths, 164,000 were from sickness, accident or other causes not associated with battle. The Confederate estimates for battle may be fairly accurate, but those for sickness are almost certainly underestimated. Indications are that on both sides two to three men died from sickness for every one killed in battle. The total dead among Civil War soldiers is estimated at 618,000 — more than for any other conflict in American history.

Contributing Factors

Lack of essential medicines, archaic methods of treatment, ignorance, and laxity of camp discipline led to an untold amount of disease and suffering among Civil War soldiers. Defective organization and training of medical personnel, deficient transportation arrangements, and inadequate hospital facilities also played prominent roles.

Reasons for the high mortality rate from sickness included ignorance of the causes of disease, haphazard induction procedures, deficiency in the soldiers’ diet, and poor sanitation practices. Sometimes the water supply was close to refuse deposits or latrines, making water unsafe for drinking. As for shelter from the elements, soldiers adopted a terminology in which “dry” meant “not absolutely wet” and “perfectly dry” meant “somewhat damp, but not soaked through.” Thus, cases of bronchitis and rheumatism were numerous, and sometimes fatal.

Scarcity of soap and the difficulty of bathing added to body filth, and swarms of pests — flies, mosquitoes, chiggers, fleas and the ever-present body lice — frequently made life challenging for the soldiers.

Volunteers in the early years of the war were particularly susceptible to disease. Many came from the country, where they had avoided childhood diseases more prevalent in urban settings and thus were not naturally immune to measles and other common ailments. Measles often led to pneumonia, sometimes proving fatal, and antibiotics and penicillin were far in the future.

Common Ailments

Latrine beside stream at the notorious Andersonville prison camp (Georgia).

Dysentery and diarrhea were the most prevalent camp diseases. Chronic cases of these sometimes led to permanent disability and discharge from the army and could even be fatal. Poor diet and exhaustion were major factors in the cause of both, which proved more rampant and much more often fatal to Confederates than to Union troops.

Malaria was a common disease in camps in the South. Its cause was not known, so proper precautions were rarely taken. Typhoid fever was less common than malaria, but was far more fatal. It may have caused one-fourth of the deaths from disease in the Confederate army.

"Social Diseases"

Sexually transmitted diseases were common, especially when troops were stationed near cities and when furloughs gave individuals opportunities to “roam.” Doctors had no real treatment for such diseases as syphilis and gonorrhea until decades into the future, and much of the time the worst effects did not show up until years after the soldier was first contaminated. Contagion remained high, however, and many wives and children North and South later paid the price for soldier “wanderings.” During the war most surgeons treated outbreaks of “French Fever” with old standbys such as “blue mass” (a concoction largely of mercury and chalk, also called “blue pills”) or special concoctions of individual doctors — none of which proved effective.

Remedies and Protocol in the Field

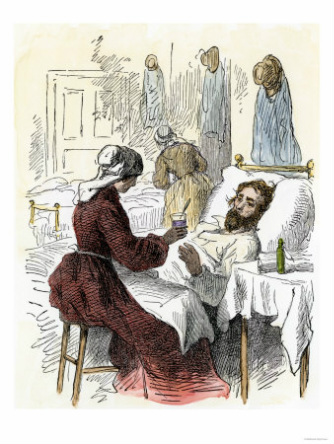

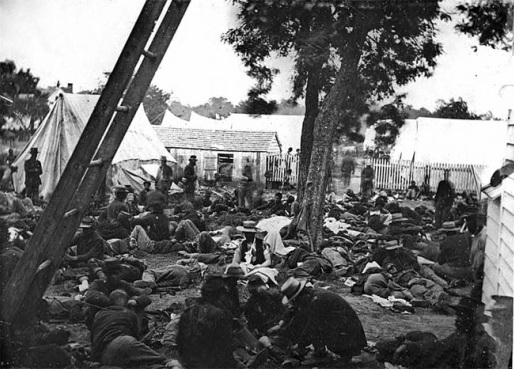

Field hospital near Richmond, Virginia.

Treatments for various ills were of great variety. American medicine was in a state of transition and the situation in the Confederacy was further complicated by the Union blockade that required Southern physicians to find substitutes for many accepted medicines. Alcoholic beverages, administered straight or mixed, were regarded as panaceas for many diseases, especially for bronchial infections. Mustard plasters also were a favorite treatment in such cases. Quinine was the generally recognized remedy for malaria, but it became scarce in the South during the war as the blockade became more effective.

Sick call was held daily, usually soon after morning roll call. Ailing soldiers would be checked by surgeons or their assistants. According to the malady, the soldier would be administered blue mass, a ball of opium, or some home-made remedy brewed from various tree barks. If available, quinine was administered for malaria and some other fevers. Astringents or purgatives often were used to treat diarrhea and dysentery, treatments that more often than not added to the misery and length of the illnesses. And, of course, whiskey or other forms of alcohol frequently were used to treat almost any illness. Except for the alcohol, much of the medicine was discarded by individual soldiers as useless or even harmful.

The worst cases were sent on to field hospitals, usually set up according to brigade or division and often anywhere from one to five miles behind the lines. Thus, the sick soldier usually made the trip by ambulance or any other wheeled vehicle available.

Hospital Care

Capt. Sally Tompkins

Soldiers generally looked with abhorrence on any hospital, whether in the field or in cities. Operations were often excruciatingly painful because of a scarcity of anesthetics and dullness of scalpels. Clothing and bed covers were frequently inadequate, and sanitary conditions left much to be desired.

There were a handful of exceptions. Following the first battle of Manassas in July1861, 28-year-old Sally Tompkins opened the Richmond home of Judge John Robertson as a hospital. Under her supervision, the hospital treated 1,333 soldiers in four years with only 73 deaths—the lowest mortality rate of any military hospital during the war. Her hospital was so efficient that, when the Confederacy late in 1861 began to organize hospitals under military command, President Jefferson Davis commissioned her a Captain in the Confederate cavalry so she could continue to supervise her hospital. Tompkins accepted the commission, but refused payment for her services. She was the only woman officially commissioned an officer in the Confederate army.

Good Care and Fresh Air

Another notable hospital with considerable success was Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond. The largest and most famous medical facility in the South during the Civil War, it admitted 78,000 patients suffering from battlefield wounds and diseases. Its mortality rate was about 9 percent (with 6,500 to 8,000 deaths total), much lower than most hospitals during the war. Even the best-staffed and equipped Union hospitals had a mortality rate of at least 10 percent. Chimborazo Hospital was constructed in late 1861 on a 40-acre plateau that stood on a high prominence with bluffs reaching down toward the James River. It apparently was named for Mount Chimborazo, a volcano in Ecuador.

Chimborazo Hospital’s success was attributed to a combination of an open-air pavilion-style design, comparatively good quality of care, and innovative practices. The first 1,000 patients arrived in October 1861, but the facility was filled beyond capacity during the Seven Days campaign around Richmond in 1862, when large Sibley tents (occupied by 8 to 10 patients) were erected outside the buildings. By late July 1864, many of the sick and wounded in Chimborazo were transferred to other hospitals in the city established for patients according to state residence.

Chimborazo Hospital’s success was attributed to a combination of an open-air pavilion-style design, comparatively good quality of care, and innovative practices. The first 1,000 patients arrived in October 1861, but the facility was filled beyond capacity during the Seven Days campaign around Richmond in 1862, when large Sibley tents (occupied by 8 to 10 patients) were erected outside the buildings. By late July 1864, many of the sick and wounded in Chimborazo were transferred to other hospitals in the city established for patients according to state residence.

Home Care

Judge John Robertson's house became a full-fledged hospital. Many other households welcomed a few convalescent soldiers.

Richmond’s private citizens were especially important in caring for wounded and sick soldiers before military hospitals were organized along state lines by late 1862. Many Confederates wounded at such battles as First Manassas (Bull Run) in July 1861 and during the fierce fighting of the Seven Days around Richmond in June and July of 1862 were taken into Richmond homes for treatment and convalescence when regular hospitals were overwhelmed by numbers. A number of Richmond women at those times and throughout the war also volunteered their services at regular hospitals.